Didi Dunin

Science of Chess: Seeing the board "holistically."

Better players may read a chessboard in the same ways we recognize faces.If I had to pick one idea about chess expertise that fascinates me the most, I think that would have to be the possibility that strong players see the board differently than mere patzers like myself. I've written about various aspects of this before, describing what we know about theeye movements that strong players make when looking at chess positions andthe largerperceptual span they appear to have for pieces on the board. These are some intriguing specific examples of how chess expertise changes the visual processing players engage in as they look at a game. To me, these results are interesting because they make the nature of expert-level play explicit in terms of visual and cognitive processes and also because they occupy a spot where the science of chess intersects with my own research interests in vision science.You see, in my lab at NDSU, we spend a lot of time doing experiments to understand how experience and visual expertise may affect visual recognition, with a particular focus on face recognition.

Why faces? If you're wondering why I spend so much of my professional life on this one topic, you're not alone. On my first day as a post-doctoral researcher, one of my new lab-mates asked what I worked on, and my answer elicited a drawn-out sigh and a look of mild disappointment. "Another face person," said the inimitable Dr. Jenny Richmond, "I still don't get the big deal. Why is everyone so excited about faces all the time?" I defended myself as best I could (and I should note that we were and are great friends!), but it's a fair question. Even after doing research on the topic for 20 years or so, I get why it seems surprising that someone would focus that specifically on what seems like one little corner of psychology.

The thing about faces that I think is so interesting is that they are probably the best example of a class of visual stimuli that most of us have extensive expertise with (save for individuals with face-blindness, or prosopagnosia) AND that we see differently than other objects in measurable ways. And here's where the stuff I think about in the lab runs smack into the Science of Chess! The target article I'd like to tell you about offers some evidence that the way expert players visually process chess positions may have a strong resemblance to how all of us (or at least most of us!) process faces. To get us started examining what that commonality between chess and faces might be, I need to tell you a little bit about face recognition first, and explain why (and how) we think it works differently than other kinds of visual recognition.

Processing faces as a whole, (not by parts!)

So what is the big deal about faces and face recognition? There are a few reasons that faces stand out from other classes of visual stimuli. One that's rooted in cognitive neuroscience is the existence of specialized cortical areas (like the fusiform face area, or FFA) that contribute to face recognition. If the brain has devoted some specific areas to processing these images, surely that means there is some way that they're unique, right? For my part, even though I got my start as a researcher working in a lab that did tons of exciting work on these brain areas, I'm still much more interested in the behavioral features of face recognition that I think make an equally compelling case for faces to be considered an interesting special case of visual recognition.

You're (probably) very good at recognizing faces

This first one may seem less than exciting, but I think it's very important. Depending on your environment, you probably have a fairly large collection of faces that you are capable of naming, telling apart from one another, or at least recognizing as people that are familiar to you even if their name escapes you. By "large," I mean something like 5,000 faces or so. Not only do you individuate this large collection of faces, you do so subject to some unique types of variability that other objects aren't subject to: Faces do all kinds of non-rigid deformation, for example, when people talk, smile, or furrow their brows. Not only can you recognize people when they twist their facial features around this way, you can even use those movements to do things like read lips, recognize emotions, or make guesses about people's mental states. If nothing else, that's a great bag of tricks that's hard to match with other types of objects.

Image credit: J. Campbell Cory, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Image credit: J. Campbell Cory, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Not only are you capable of recognizing an awful lot of faces, you can also do a lot of good work with very little visual information. My graduate advisor, Dr. Pawan Sinha, has done many studies examining how good you are at recognizing faces when they are degraded by blur and noise, for example. It turns out that even when familiar faces are terribly blurry, you tend to do quite well anyway, demonstrating how robust your face recognition mechanisms are to fairly dramatic changes in appearance quality. To give you my favorite example of this, I have to show you what might be the most glorious case of degraded face recognition in the wild.

Back in 2018, a man in Lancaster, Pennsylvania (my home state, but not my hometown!) allegedly took advantage of an employee stepping away from their station by taking over their spot and swiping some cash when the opportunity presented itself. Obviously the man left in a hurry after doing so, but some eyewitnesses did apparently think that something looked a little suspicious and when questioned were able tohelp come up with a sketch of the suspect. Dear reader, here is that sketch:

I think there's a decent chance you may have laughed a little at this sketch, and if so I don't blame you. The thing is that despite what seem like the obvious shortcomings of this sketch, they caught him! Someone saw that drawing and it was just enough for them to realize that they might know the guy the police were looking for and they called it in. If this doesn't convince you that your face recognition is pretty impressive, I'm not sure what would.

Recognizing upside-down faces is surprisingly hard.

So your face recognition is quite good and that might be one reason to suspect that it's different somehow from the other kinds of visual recognition you do. This isn't enough, however: Just because you're particularly good at one version of a task doesn't mean you do something qualitatively different to complete it. Your remarkable abilities at recognizing faces may just mean that the same tools you apply to recognizing other objects are just being used to their utmost in this case. Do we have evidence that you might actually use some truly different tools for faces than for other objects?

In fact, we do! One classic result in the face recognition literature concerns something a little curious that happens when you turn faces upside-down. Doing so keeps a lot of things intact in the original image, but obviously disrupts many others. If we measure how much this changes your ability to tell two objects (like chairs or shoes, for example) apart, many studies have found that you tend to do a little bit worse, but not terribly so. Turn faces upside-down, however, and something different happens: You get much worse. I could show you some profoundly exciting bar graphs about this, but instead I'll refer you to a more dramatic demonstration of this phenomenon: The Thatcher Effect. First, take a look at the two images below, which each depict former British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. They are both upside-down, of course, and you can probably tell that there is some kind of difference between the two. My guess, however, is that even if you can sort of work out what we've done to one of these pictures that makes it different than the other, it isn't having a huge impact on you.

Turn both images back to right-side-up, though, and the situation is probably much different. Now one of these faces probably looks absolutely grotesque while the other is obviously just fine. The classic account of what's happening here is that the upright faces can be processed very effectively by your face recognition mechanisms, making the local inversion of the eyes and mouth immediately apparent and highly troubling. Turning these images upside-down demonstrates just how much less effective those mechanisms are at relaying the appearance of the inverted pictures - a huge different in the upright faces turns into a visible, but less affecting difference in the inverted ones.

The big idea here is that this is an important clue that the tools you use for most other objects may be different in some qualitative way: Those tools can do much the same work on an upright and an inverted picture, but the tools you use for faces cannot! I need to tell you before we move on that this specific effect remains something we're learning about and there is more nuance to this than I'm making room for here, but for our purposes it leads us nicely to what we need to connect face processing to chess processing.

You recognize faces holistically (whatever that means!)

The inversion effect suggests that there might be something different about the way we process faces compared to other objects, but what is that difference? Another class of behavioral results from the face recognition literature has helped make this more clear, and this is where we need to go next to set the stage for our target article about chess. Together, these effects suggest that we recognize faces by processing them as holistic patterns, which doesn't seem to be true for other objects. What does that mean, exactly? To be blunt, we're still working that out, but the effects I'm about to describe give us some vital clues.

The part-whole effect

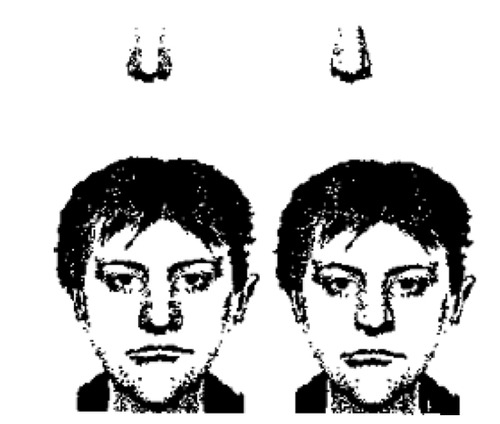

First, let me tell you about something called the part-whole effect, which was first reported by my friend and colleagueDr. Jim Tanaka and Dr. Martha Farah. In their study, they presented participants with a recognition task that required them to tell faces apart that only differed in one facial feature (let's say the nose - see below). People tended to do quite well at learning to tell these faces apart, and you can test this by showing them the faces a little later and asking them to choose the one that matches a name they learned ("Which one of these is Larry?").

But here's the interesting part: Those two faces only looked different because they had different noses, right? Given that, what happens if we don't show our participants the whole face to test their recognition, but just show them the noses instead? ("Which one is Larry's nose?"). The first interesting surprise in this study is that telling just the two noses apart after learning about them from whole faces turns out to be extremely difficult! Even though this was the crucial part of the picture for distinguishing the faces, people need to see the nose in the context of the whole face to reliably recognize who is who.

The second interesting surprise here is that if you play exactly the same game with another kind of object, it works very differently. Instead of faces that only differ by a nose, let's use houses that only differ by a door. We can use the same kind of learning task and ask the same kinds of questions afterwards ("Which is Mike's house?" or "Which is Mike's door?") and in this case, it's not a problem to pick the right house OR the right door. What's going on? One account of these different outcomes is that objects like houses may be broken down into lots of parts (like doors, windows, etc.) for recognition, but faces are not broken down into parts like the eyes, nose, and mouth. Instead, faces may be recognized by using the whole face pattern at once, making it difficult to make good recognition judgments about any small parts of the pattern.

This is one of those results that I still think about a lot, even though it's now more than 30 years old. In particular, it still makes me wonder about this thing people do all the time when they judge family resemblance and appeal to specific parts of the face: "She's got her mother's eyes!" people will say, or "That's her Great-Uncle Kevin's nose!" Anecdotally, at least, people seem remarkably confident about these despite a lot of data that indicates we're awful at judgments like this. If you want a fun way to experience just how tough these judgments are, I'd encourage you to try out the brilliant Eye-Q game developed by Didi Dunin, a PhD student in Psychology at the New School in NYC. In Didi's game (pictured in the thumbnail for this post) you hold up a card with a celebrity's eyes in front of your own, placing these familiar eyes in the context of your face. Because of whatever is happening that drives the part-whole effect, it is MUCH tougher to figure out whose eyes you're looking at!

The composite face effect

The Eye-Q game sets the stage nicely for talking about one more effect that we need to understand the face-chess connection being made in our target article. I say this because something you'll experience if you play the game is that putting the celebrity eyes in the context of a new face makes the eyes look sort of...different. That is, you may see the shape or spacing of the eyes a little differently if they appear in the context of one person's face vs. another and this obviously complicates things for you. But what's going on with this? The part-whole effect suggested we'd be bad at recognizing parts on their own, but it didn't say anything about parts looking different in different settings!

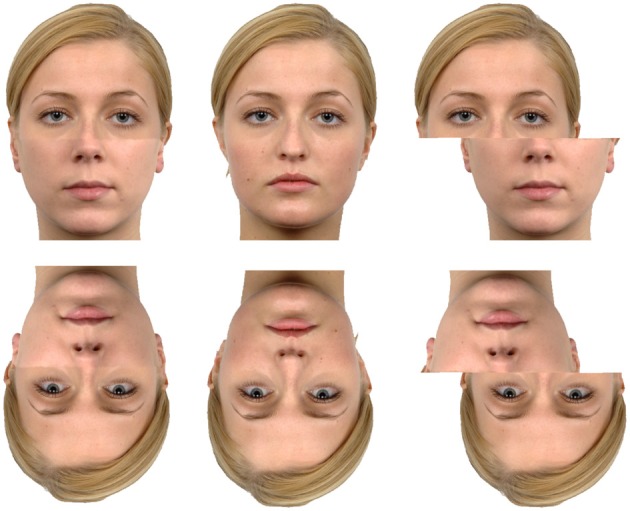

Enter the composite face effect (or CFE), another classic behavioral effect in face recognition that has been studied for years and suggests that we're doing something to process face images that involves measuring the whole pattern at one go. The basic phenomenology of the CFE is as follows: Imagine I give you two faces to look at, and I ask you to only worry about the top half of each one. That is, your job is to completely ignore the bottom half of these pictures and only tell me if the two top halves I'm presenting you with look the same or different. The tricky bit is that I am going to play around with the bottom half of these images to try and complicate things for you. In particular, the crucial result that more or less defines the CFE is that identical top halves of face images tend to look different if I give them different bottom halves. You can see an example of this below - on top, the left and right images are exactly the same, but the different bottom halves may give you the sense that they look a little different. In the lab, we can measure this effect by comparing your accuracy for judging whether those top halves are the same or different under these circumstances and compare that to your accuracy when there is either no bottom half messing with you at all, or a misaligned bottom half.

Figure 1 from Watson (2013). All the top halves in these pictures are identical, but the first two in the top row probably look different to you due to the differing bottom halves. Misaligning the bottom half or turning the faces upside-down tends to reduce this illusion

What we think is happening here (and in the part-whole effect) is that your visual system is doing something to measure facial appearance that is either holistic (using the entire pattern) or at least at a larger scale than these small parts of the face. The result is that the appearance of the bottom half ends up tangled up with the appearance of the top half in a way that can't really be undone without some kind of external cue like mis-aligning or inverting the image. This is also what we think is happening in the Eye-Q game of course, which relies on this illusion to make an already-difficult party game even more challenging. The appearance of your face similarly gets entangled with the appearance of the eye, making it harder to match the celebrity eyes you are seeing in the game to your recollection of what those eyes look like in the context of the original face.

Together, all these results help make a strong case that faces aren't just interesting because they're socially important or because you have a lot of skill at recognizing them. Faces are also important because they are a nice example of how some objects and patterns may be perceived and recognized differently. Whether or not these kinds of differences are solely confined to faces or may apply to other objects you either gain extensive expertise with or have to recognize at particular levels of granularity has been an ongoing debate in the field for some time. These results I've described that are measurable for face images and the possibility that large-scale or holistic processing may be applied to other images leads us very nicely into our target article, which is an attempt to look for evidence of holistic processing for chess positions.

Seeing the board holistically

The question that the researchers behind this study wanted to answer was whether or not strong chess players might also be processing chess positions holistically in the same way that the rest of us (who are strong face recognizers) process faces holistically. At first glance, this might seem like a somewhat odd connection to make, but remember: One perspective on why we see holistic processing for faces is that it may be a type of visual processing that shows up for other patterns you recognize at an expert level. Chess masters looking at chess positions would certainly qualify in that regard, andI've written before about the evidence suggesting that stronger players are capable of processing larger regions of the board at once than weaker players.

To look for evidence of holistic processing in chess masters, the authors of this study went looking for a version of the CFE with face images and with images of chess positions. In both case, the images were cut in half with a horizontal line, and the top and bottom halves of both kinds of images could be independently manipulated. On congruent trials, the status of the bottom halves that participants were asked to attend to would match the status of the top halves of the images they were considering. On incongruent trials, the status of the bottom would be different from the status of the top - note that this is a slight variation of the CFE as I described it, but the overall idea is the same. An observer who is not processing these images holistically should be able to "tune out" the irrelevant part of the images and do about as well on congruent trials as incongruent trials. By comparison, a holistic processor should find incongruent trials harder to deal with.

Figure 1 from Boggan et al., (2011). Both chess positions and faces were manipulated so that top and bottom half appearance could either be congruent or incongruent. Holistic processing of either stimulus should lead to greater difficult on incongruent trials.

The task the authors asked their participants to carry out is a little more complex, too, and makes it possible to ask some interesting questions about possible interference between chess processing and face processing. Participants were asked to view interleaved chess and face images, responding on each trial about the match or mismatch between the image they could see now compared to the image they saw two images ago. By constantly interposing an image of the other type between the two images you were comparing on each trial, the authors were hoping to see evidence that holistic processing of one category might get in the way of holistic processing of the other one. This would mean that chess experts might show a very strong CFE for chess boards, but a weaker one for faces.

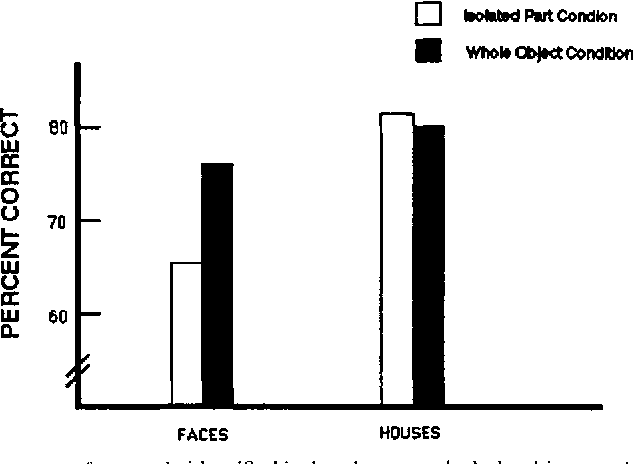

The first big question though, is whether or not there is a "composite chess effect" at all! Do players of any strength process chessboards in a manner that seems holistic, at least as measured by this effect? In the figure below, you can see the average accuracy across player groups for congruent and incongruent same/different judgments (indexed here with a quantity called d-prime) as well as the difference between congruent and incongruent performance. That latter difference score is a quick way to see if performance with each type of image seems holistic: A tall bar in this graph means that the incongruent trials were harder than the congruent trials, which should only happen with greater holistic image processing.

Figure 2 from Boggan et al. (2012). The size of the composite effect for face and chess images is evident in both the raw d' scores (top row) and the difference scores between congruent and incongruent accuracy (bottom row). Strong players have a clear composite effect for face AND chess image, while novices do not.

The punchline from these results is that the Expert players (ELO ~1900-2700) do indeed appear to process faces and chess positions holistically, but weaker players don't! By itself this is a compelling result that indicates a way in which stronger players see the board in a different way than weaker players. What is that difference, though? I find it a little easier to think about this in terms of what the weaker players (like me) may be seeing, or perhaps more importantly, what they are NOT seeing. The lack of a strong composite effect for chess positions in the weaker players suggests that rather than visually processing the board at a larger spatial scale, these players are limited to taking in visual information in relatively small pieces - a bit like "tunnel vision" if you will. In other visual tasks, that failure of larger-scale processing means there is a sort of additional step you need to take to integrate or combine the parts that you see into a larger whole, which is one more error-prone process that can be inaccurate or slow. This all reminds me very much of my recent conversation with CM Can Kabadayi about "Sniper Bishops" and blunders of misperception - holistic processing of the board almost certainly helps a player notice long-range threats over the board, and the lack of it makes us patzers much more prone to nasty surprises.

There are a number of other interesting results we could talk about, but I want to highlight just one more for you that I think is particularly neat. Remember that part of the idea behind the interleaved faces and chess positions that the researchers showed their participants was to look for evidence of interference between chess and face processing. Another intriguing way that they looked for evidence of some sort of competition between visually processing faces and chess boards holistically was examining the correlation between experts' starting age for chess and the magnitude of their composite effects. While this did correlation was NOT significant for a composite chess effect, it did reach significance for the composite face effect! Their data shows that starting chess at a younger age led to a smaller composite face effect, perhaps indicating that increased expert (holistic) processing of chess boards incurred a bit of a cost to expert face processing.

What does a position look like?

These results suggest that strong chess players may "see" chess positions differently than weaker players, and gives us a word ("holistic") to describe what the difference is. That gives us some idea of how board vision works differently with increased expertise, but what I'm still interested in (and what these data don't speak to) is what that actually means in terms of the experience of looking at the board. What does a master subjectively experience that's different from what I see? What (if anything) actually appears different to them? To be fair, these are questions that are always hard for a vision scientist - we measure things like accuracy, speed, and the effects of image manipulations on these data, but we don't know how to work from those back to experience itself. For now, this study (and others like it) give us a tantalizing hint that there's something different there worth trying to understand more fully.

Support Science of Chess posts!

Thanks as always for reading! If you're enjoying these Science of Chess posts and would like to send a small donation my way ($1-$5), you can visit my Ko-fi page here: https://ko-fi.com/bjbalas - Never expected, but always appreciated!

References

Boggan, A. L., Bartlett, J. C., & Krawczyk, D. C. (2012). Chess masters show a hallmark of face processing with chess. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024236

Murphy, J., Gray, K. L., & Cook, R. (2017). The composite face illusion. Psychonomic bulletin & review, 24(2), 245–261. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-016-1131-5

Sinha, P., Balas, B., Ostrovsky, Y., & Russell, R. (2006). Face Recognition by Humans: Nineteen Results All Computer Vision Researchers Should Know About. Proceedings of the IEEE, 94, 1948-1962.

Tanaka, J. W., & Farah, M. J. (1993). Parts and wholes in face recognition. The Quarterly journal of experimental psychology. A, Human experimental psychology, 46(2), 225–245. https://doi.org/10.1080/14640749308401045

Thompson P. (1980). Margaret Thatcher: a new illusion. Perception, 9(4), 483–484. https://doi.org/10.1068/p090483

Watson T. L. (2013). Implications of holistic face processing in autism and schizophrenia. Frontiers in psychology, 4, 414. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00414

You may also like

NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: Winning Streaks, Losing Streaks, and Skill

Being a patzer is hard, and it can be even worse when loss follows loss! CM HGabor

CM HGaborHow titled players lie to you

This post is a word of warning for the average club player. As the chess world is becoming increasin… Vlad_G92

Vlad_G92Obituary: GM Daniel Naroditsky (1995-2025)

Daniel Naroditsky passed away at the age of 29 in Charlotte, NC, where he resided since 2020. matstc

matstcA Chess Metric: Ease (for Humans)

“I know the engine evaluation but how easy to play is this position, really?” NDpatzer

NDpatzerScience of Chess: What does it mean to have a "chess personality?"

What kind of player are you? How do we tell? Lichess

Lichess